Bilingual Books in Spanish

By Leylha Ahuile

In the past few years, a fundamental shift has taken place in the way we think about language in the U.S. The Census Office estimates we will have 138 million Spanish speakers by 2050, making the U.S. the country with the largest Spanish-speaking population in the world. This statistic, combined with the world becoming increasingly connected and the realization that jobs are growing more global in scope than ever, has prompted an increase in the number of dual-language education programs—in which students are taught literacy and content in two languages—across the country.

Parents, regardless of race or ethnicity, want to provide their children with the best possible tools for the future, and being fluent in more than one language is becoming more common for students, as it’s seen as a distinct academic advantage. Several studies, and information from the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, demonstrate that the benefits of learning a second language can include higher academic achievement on standardized tests and increased cognitive development and abilities. All of this has resulted in a growing demand from parents and educators for bilingual books.

Publishers heard a whispering need for bilingual children’s books in the 1970s and began offering translations of such children’s classics as Little Red Riding Hood and Snow White. By the ’80s, many of those classics were replaced by books such as La Llorona/The Weeping Woman by Joe Hayes or the Maximilian series of books by Xavier Garza. As the appetite for bilingual books has grown, readers are not just looking for more titles, they’re also seeking books that are culturally relevant. According to Katherine Del Monte, director/publisher at Lectura Books, “Cultural relevance and including heritage languages in education and materials is not new but is now coming into its own. The publishing world is waking up to the market opportunity, as well as to the change in demographics, especially in the children’s book market.”

Demographic Shifts

In the past, bilingual books were mainly used by Spanish speakers who were learning English. By the mid-’70s, small independent publishers were publishing bilingual books to meet the needs of educators and librarians who had begun servicing a wave of immigrants from Latin America. In 1975, there were 12.2 million Hispanics, making up 6% of the U.S. population. Today, there are almost 60 million Hispanics, making up more than 18% of the U.S. population, and according to the National Center for Education Statistics, one in four school-age children is Hispanic. With such rapid growth in population, Hispanics have become the largest minority group in the U.S. Approximately 65% of Hispanics come from Mexico, but in the past 10 years, the greatest growth has come from Central America.

These numbers reflect the need for bilingual books and also for new types of stories being shared. Most growth of the Hispanic population in the past few years has come not from immigration but from births in the U.S. This means that an increasing number of children born here are likely to be bilingual, to some extent, by the time they enter school. As children born in the U.S. have lived a very different experience than that of newly arrived immigrants, it stands to reason that the two groups are culturally distinct.

A History of Bilingual Books

When bilingual books made more inroads into schools and libraries in the 1980s, there was a great deal of debate among educators. Some self-described language purists believed that a book should present one language or the other, but not both languages side by side. Lee Byrd, copublisher of Cinco Puntos Press, pointed out that the debate has mostly subsided, but there are still librarians and educators who prefer that a book be available in both languages but published in separate Spanish and English editions.

There was also much discussion on what type of Spanish should be used, with many publishers opting for a neutral Spanish. This trend has passed, as it has been proven repeatedly that children, like adults, prefer content that reflects their culture; thus publishers today look to retain the Spanish originally used by the author. (For example, if a book is written by a Puerto Rican author, the Spanish in the book would be Puerto Rican.)

The format of children’s bilingual books has not changed much over the past 20 years. When it comes to board books, the text, in English and Spanish, is either on the same page or appears side by side on a spread. But once students progress to chapter books, they will find the Spanish on one page, then flip the page for the content in English. Some publishers, such as Lectura Books and Scholastic, publish a bilingual version, a Spanish version, and an English-language version of select titles.

In the Classroom and the Library

Bilingual books are being used in many ways in the classroom, the library, and at home. Nicolás Kanellos, founder and director of Arte Público Press, offers an overview of how bilingual books have evolved as classroom tools: “What used to be bilingual education has now transitioned into dual language education,” he says. “These are two different methodologies that service two different populations and have two different cores of educators.”

Kanellos notes that some dual-language programs start as early as pre-K and continue into senior high school, whereas bilingual programs, which were previously seen as transitional and designed to get children to speak and read English as quickly as possible, often terminate at third grade. “With dual-language education, the ideal scenario is for half the students to be English speakers and the other half to be speakers of another language,” he says. “The curriculum throughout their education is offered in either Spanish or English thus increasing all of the students’ language abilities.”

The struggles that many immigrant parents face learning English are compounded by the fact that their children are learning English at a faster rate, which can frequently lead to a lack of communication between parent and child. In order to help the entire family learn English at the same time, many have turned to bilingual books. Del Monte of Lectura Books, who also runs the Latino Family Literacy Project explains, “It makes sense to have today’s children’s books in two languages so families can read together. This, of course, helps their children’s academic achievement levels improve.”

It isn’t just schools and libraries that have identified the need for bilingual books. So have cultural organizations, such as the Children’s Museum of Houston. Kallie Benes, curriculum manager for the Department of Library Services at Houston Independent School District, considers the museum an additional resource that helps meet students’ needs. “The Children’s Museum of Houston has stepped in to fill some of the gaps,” she says. “They produce Flip Kits, a backpack with trade books, some of which are bilingual. The kits with bilingual books also include bilingual reading tips written by librarians, and activities for the family. These kits are then provided to public schools. More than 540,000 students in Houston have participated.” Benes points out that out of 180 total elementary schools in Houston, 52 have dual language programs.

In public libraries, the use of bilingual books varies depending on the library’s surrounding community. The New York Public Library, which services one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world, has more than 1,000 bilingual books that span all ages—adults, young adults, and children—and several different formats: board books, picture books, novels. “We’ve found that patrons frequently use bilingual books to practice English or learn a new language,” says Libbhy Romero, NYPL’s world languages coordinator. “The library also uses bilingual books to support such popular programs as storytime and language conversation groups for those learning English or another language,” she adds. “These materials not only provide opportunities for learning, but also expand and enhance awareness of the many cultures that make up New York City. As a result, bilingual books are also regularly included in book recommendations made by our librarians, such as the Summer Reading Early Literacy Book Lists provided by New York City’s library systems.”

Publishers in the Bilingual Marketplace

One of the earliest and best-known bilingual book publishers was Children’s Book Press, founded in San Francisco in 1975 by Harriet Rohmer. When Children’s Book Press ceased operations in 2012, Lee & Low Books acquired its list and has since brought the majority of its titles back into print. Arte Público Press, Cinco Puntos Press, and Lectorum Publications round off the top four independent bilingual book publishers. Each of these houses publishes four to five bilingual titles per year while the Scholastic en Español imprint publishes an average of 10–15 bilingual titles annually.

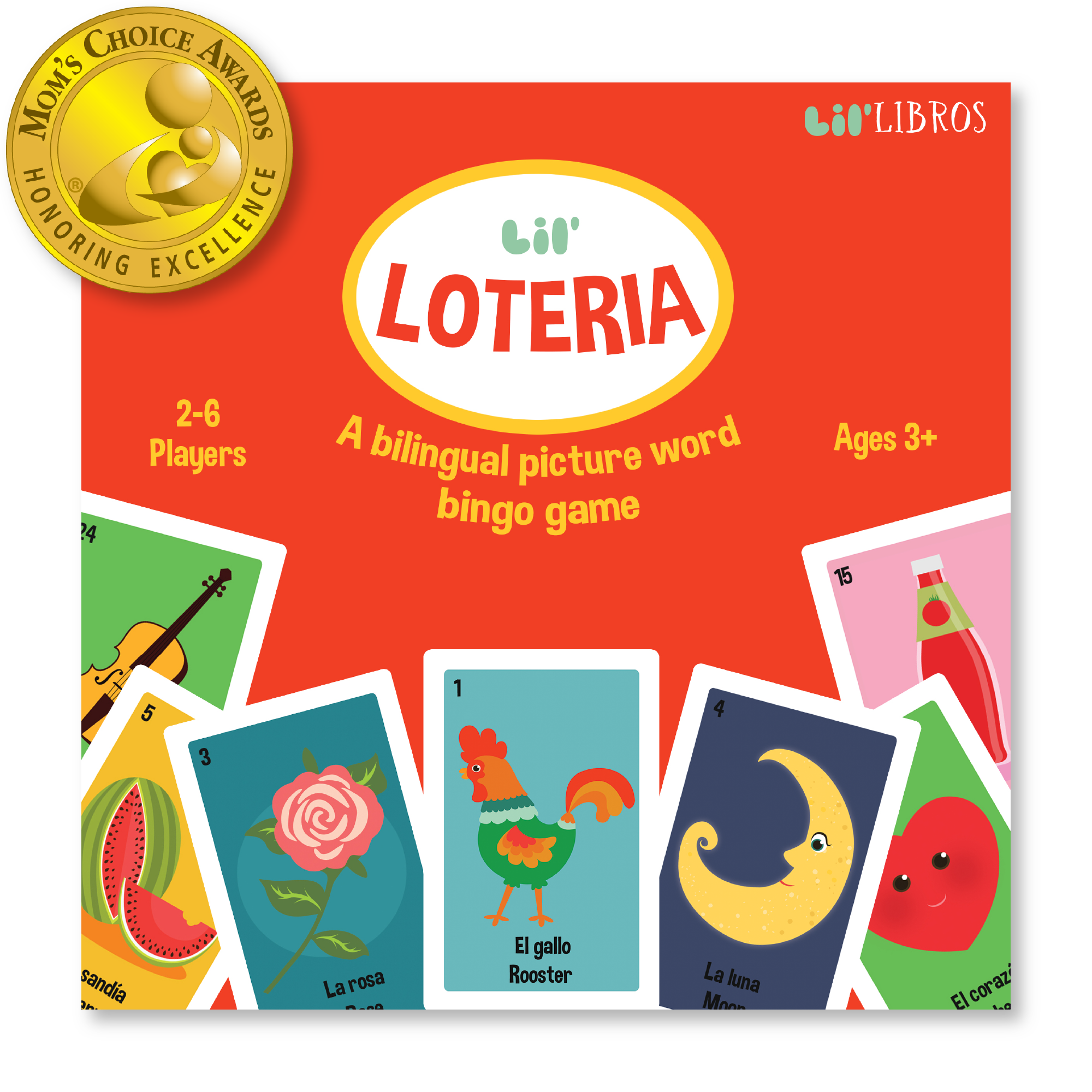

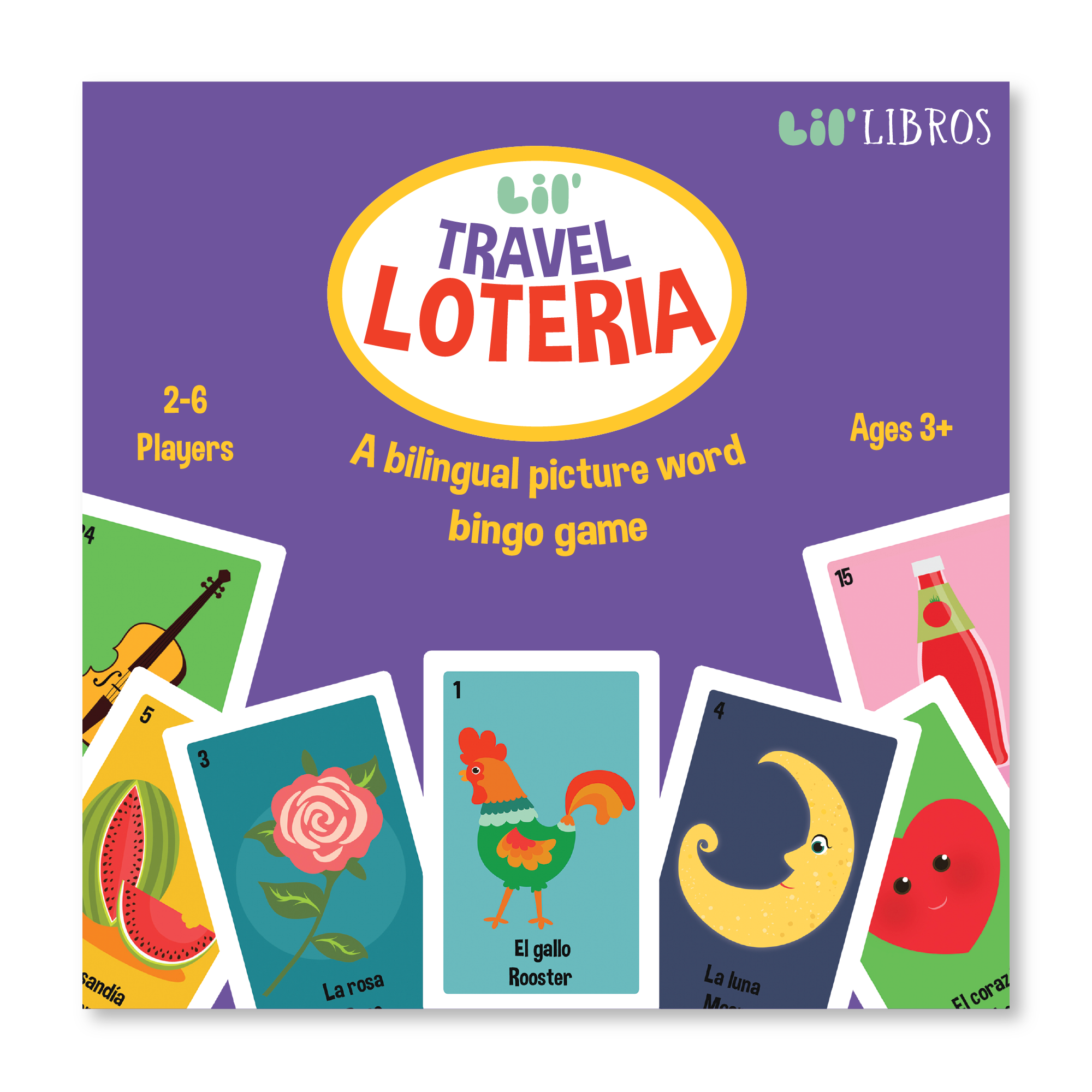

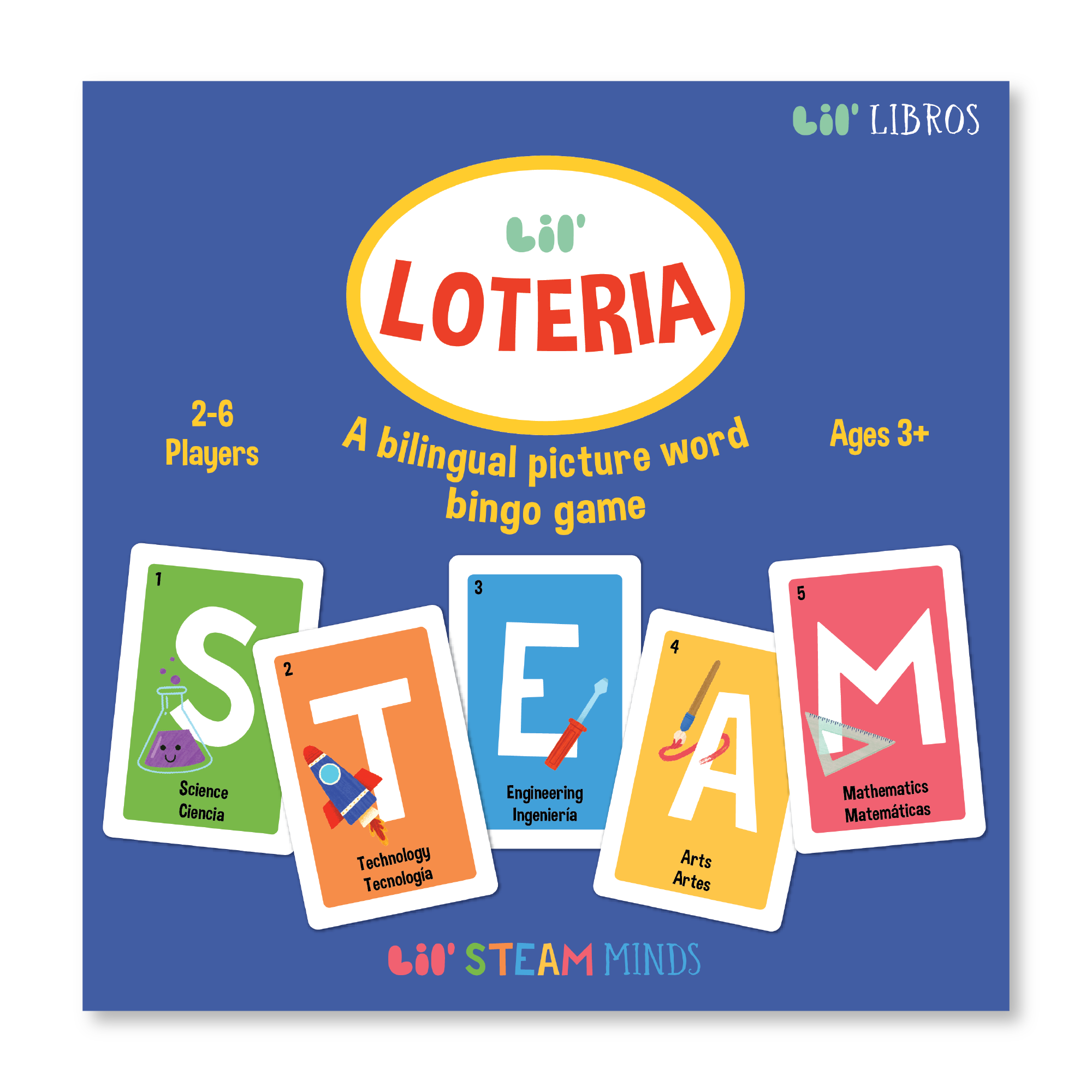

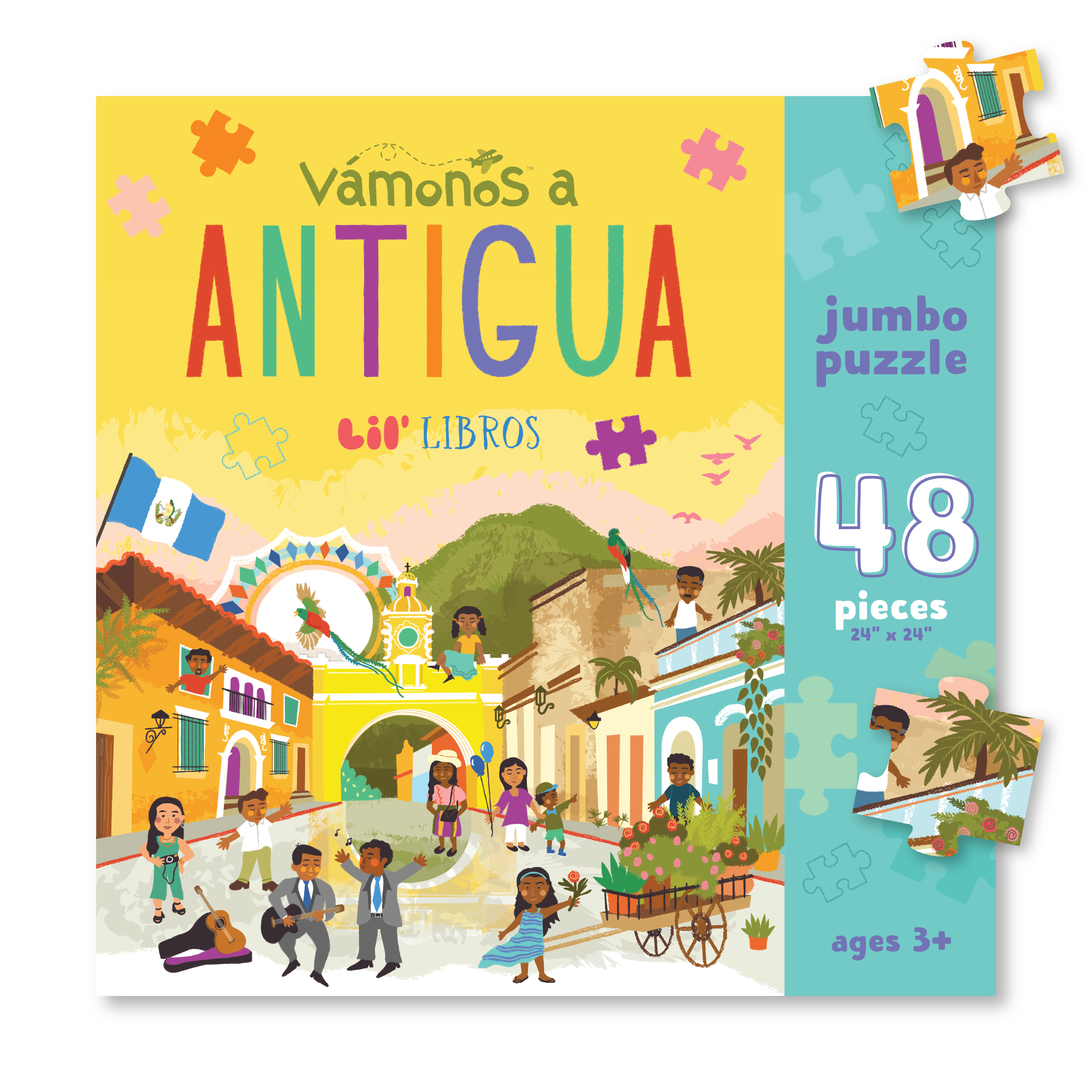

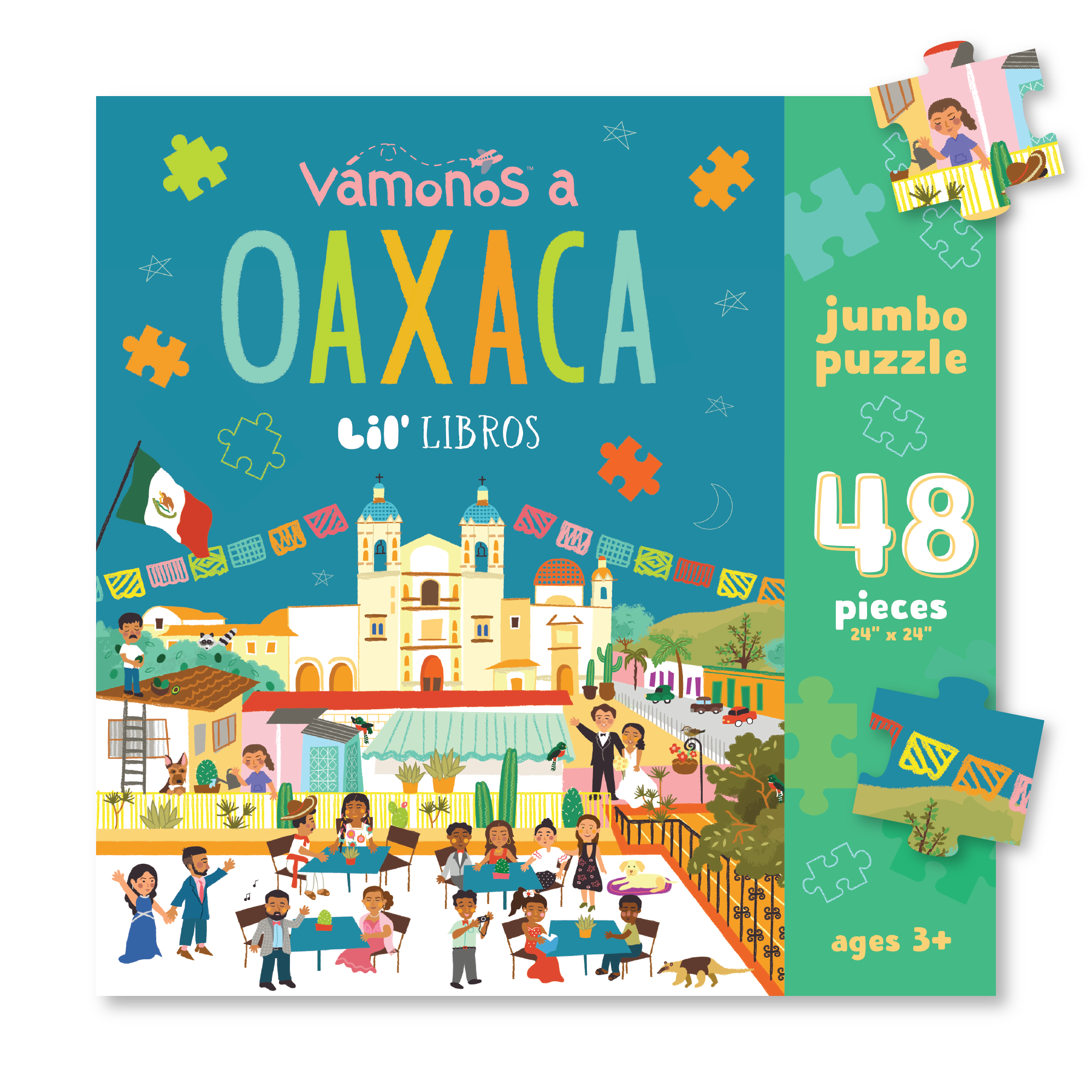

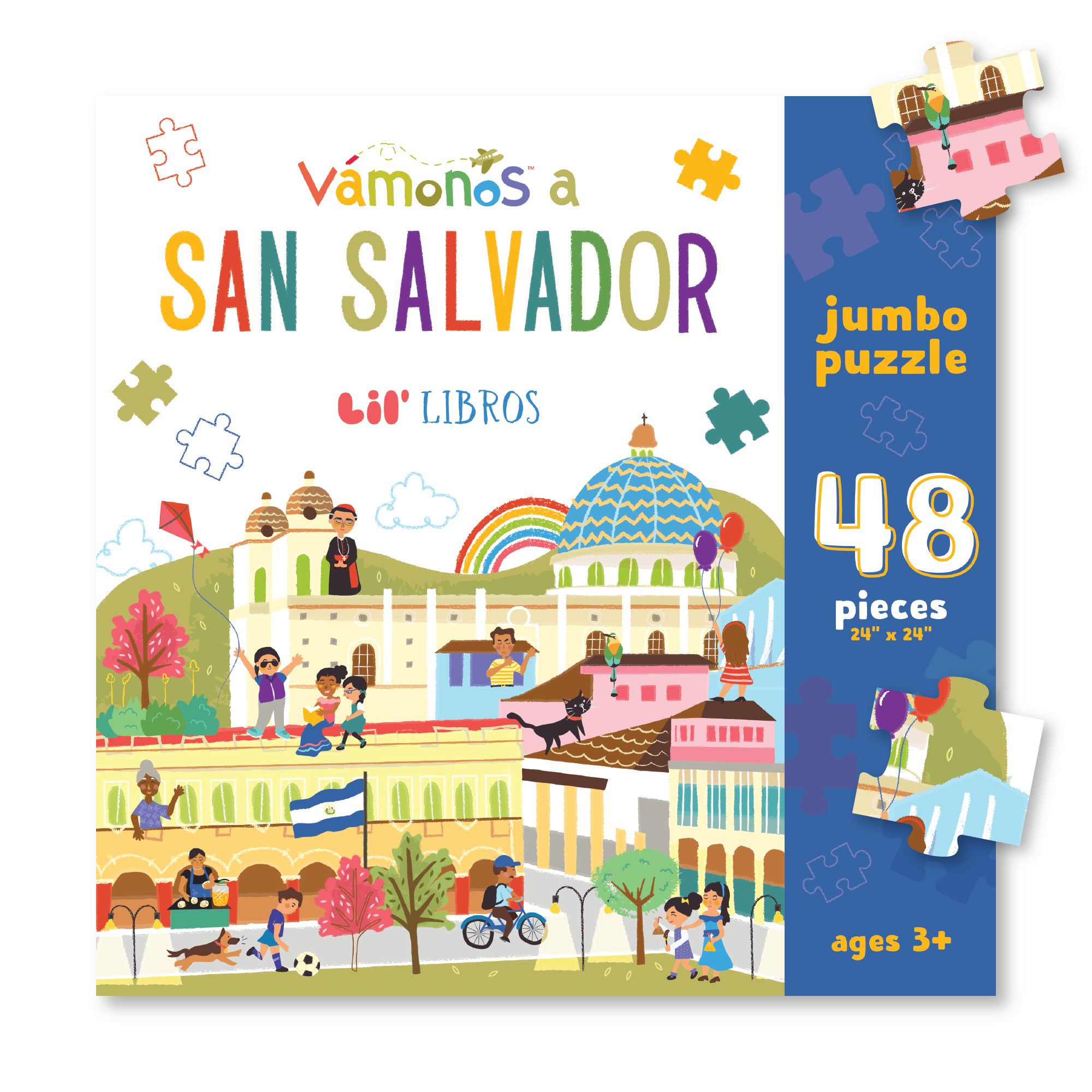

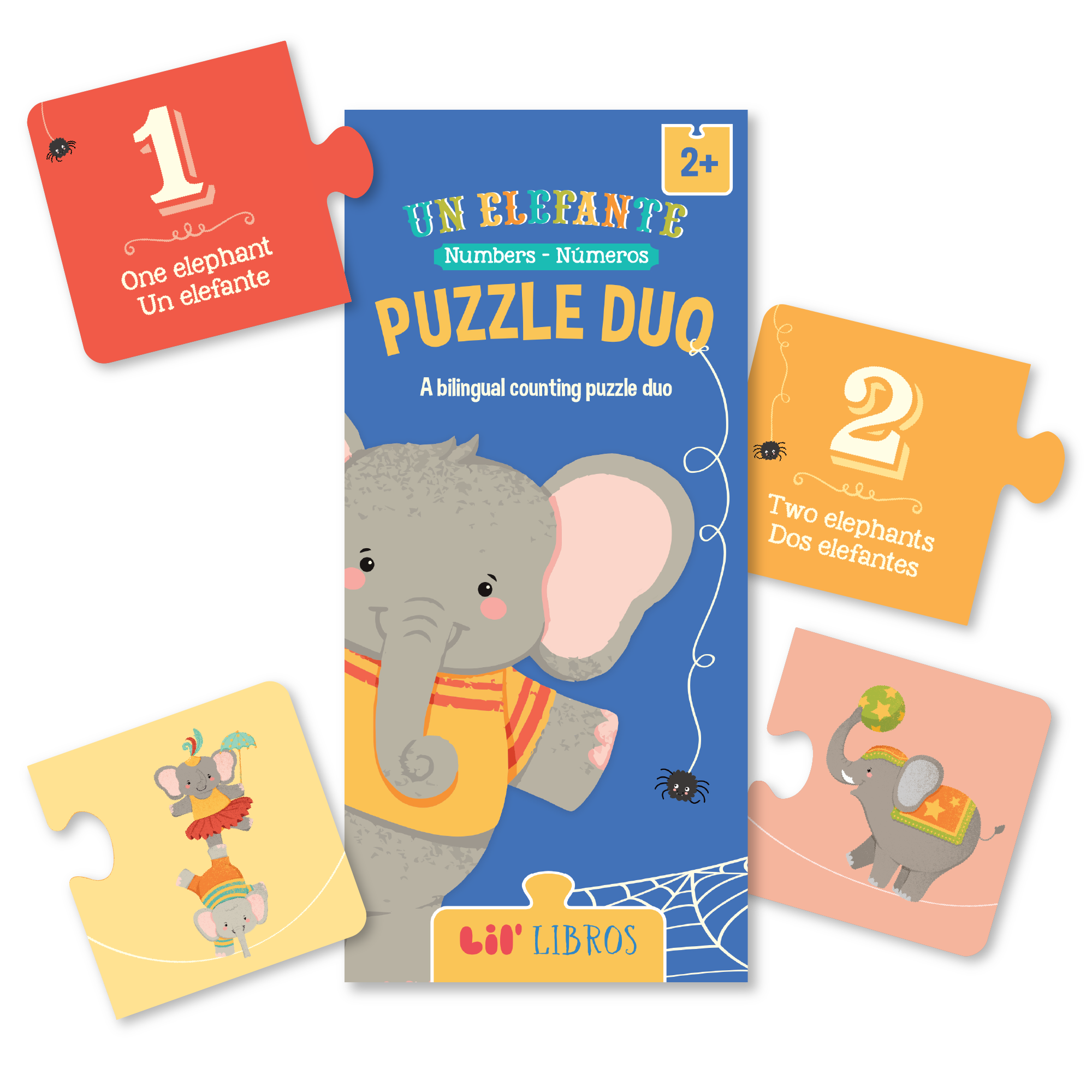

Los Angeles–based Lil’ Libros launched in 2017 with a focus on publishing board book concept titles and biographies of Latin American figures but beginning next year will expand its catalogue to include titles for readers up to age 10. Lectura Books had been on a short hiatus and published a handful of bilingual titles this year but is gearing up for 36 new titles in 2020. Arte Público Press, celebrating its 40th year as the oldest and largest Hispanic publishing company in the U.S., has 10 bilingual titles planned for 2019, which is roughly half of its children’s and YA lists.

Lectorum Publications not only publishes bilingual books but also distributes many of the books published by its competitors. The company has been around for several decades, but November will mark 10 years since current president and CEO Alex Correa became its new owner. Although Lectorum publishes and distributes a wide selection of books in Spanish, this is the first year that it launched a separate catalogue consisting only of bilingual titles.

“With the booming demand of bilingual books, we have put together a catalogue of books that offers a wide selection of bilingual books but not just in English/Spanish but also in Arabic, Chinese, Italian, French, and others,” Correa says. “As the demand for bilingual books continues to increase, we are likely to see more books available in a bilingual format.”

Romero says she has also seen more independent publishers start to publish bilingual books, and although she has not observed a substantial increase in the number of titles available, she has noticed more diverse and innovative dual language books.

Challenges and Opportunities

Publishers of bilingual books face some unique difficulties, including the cost of creating bilingual books and the challenge of selling through retail channels. Although the market has changed in many ways, bookstore owners and managers continue to place bilingual books in their foreign-language sections, where they tend to get lost.

Lil’ Libros founders Patty Rodriguez and Ariana Stein say they are thrilled to have a four-year-long partnership with Target, but many independent bookstores and other retailers are not as welcoming of bilingual titles. “It is challenging to have to convince retailers that by offering bilingual books they will not be alienating part of their customer base and are more likely to see increased sales,” Rodriguez says.

Although foreign publishers make up the bulk of the providers of books in Spanish in the U.S., U.S.-based publishers are currently meeting the need for bilingual books with little if any competition from imports. This is due in part to the uniqueness of the U.S., where many languages are spoken and taught, but also to the growing number of Hispanic children born and raised in a predominately English-speaking country. Though they might be speaking Spanish at home, their education is in English, so many parents have taken it upon themselves to make sure their children also learn to read and write in Spanish. One of the greatest opportunities U.S. publishers have is to continue to think of the shifting demographics and how that impacts students not just in the classroom but also in the home.

The general consensus of the publishers PW spoke with is that the demand for bilingual books will increase as more parents want their children to be bilingual and bicultural. Hispanic and non-Hispanic parents alike typically want their children to develop a greater understanding and appreciation of their home culture and the cultures of others.

Bilingual books aren’t just seeing success because they feature two languages on a page; they’re succeeding because of the stories they tell—and how and by whom they are being told. Most of the bilingual books that have won awards or become bestsellers or long-sellers were written by U.S. authors. It is those living in a bilingual and bicultural world who are likely to have the greatest understanding of the opportunities and challenges faced in the ever-changing U.S. melting pot.